August 16th, 2022

By Mike Petriello | MLB.com | Full Article

On Tuesday night in Chicago, two of the AL’s top Cy Young contenders will go head-to-head in MLB.TV’s Free Game of the Day. You’ll be amazed by the reinvention story of a flame-throwing righty who has been all but unhittable this year, thanks to an ERA under 2.00. You’ll marvel at how a pitcher who was a total non-factor in last year’s Astros-White Sox ALDS has risen to become the ace of his team’s staff.

And on the other side of the hill, Justin Verlander will be pitching.

That’s how good Dylan Cease has been, that he’s going to earn equal billing in this one. In the midst of what has been, so far, a disappointing White Sox season, Cease is on something like a historic run of dominance. After holding the Royals to just a single run over six innings on Aug. 12 – a game the White Sox managed to lose 5-3 anyway – he’s now made 14 consecutive starts without allowing more than one earned run. It is already an all-time record, if we set aside pitchers used only as openers. Across 14 starts: six earned runs. 103 strikeouts. A 0.66 ERA. This is Bob Gibson territory.

This isn’t entirely out of nowhere, as we’ll soon detail. The power of Cease’s raw stuff has been apparent for some time, and it wasn’t an accident that the White Sox had him included along with Eloy Jiménez and two others when they traded José Quintana to the Cubs back in 2017.

“I know his stuff is tremendous,” Verlander said on Monday regarding Cease. “It seems like he’s put it all together this year.”

He sure has, because, over his first three-and-a-half seasons, he wasn’t doing this. Somewhat like teammate Lucas Giolito’s path, Cease’s journey started with struggle and reinvention. In the first 67 starts of Cease’s career, beginning with his 2019 debut through a disastrous 7 R, 3 IP outing against Boston on May 24, he posted a 4.37 ERA. Since then, well, history.

“It is going to be a great challenge,” said Cease, when asked about Verlander and the Astros. “I’m personally looking forward to it. It’s exciting. I remember watching him a lot as a kid … just the fact that I’m here now and he’s still doing it, it’s pretty rare.”

What changed since that 5.79 ERA as a rookie, or since the mere 6.8 strikeouts per 9 in 2020 — a number that’s now north of 12 per 9? It’s not about new pitches, or better health, or any of the usual things we look at when a pitcher improves. It’s about making the pitches he had better. Let’s take a look at each of his four primary pitches to see what’s going on here.

1. THE FOUR-SEAM FASTBALL

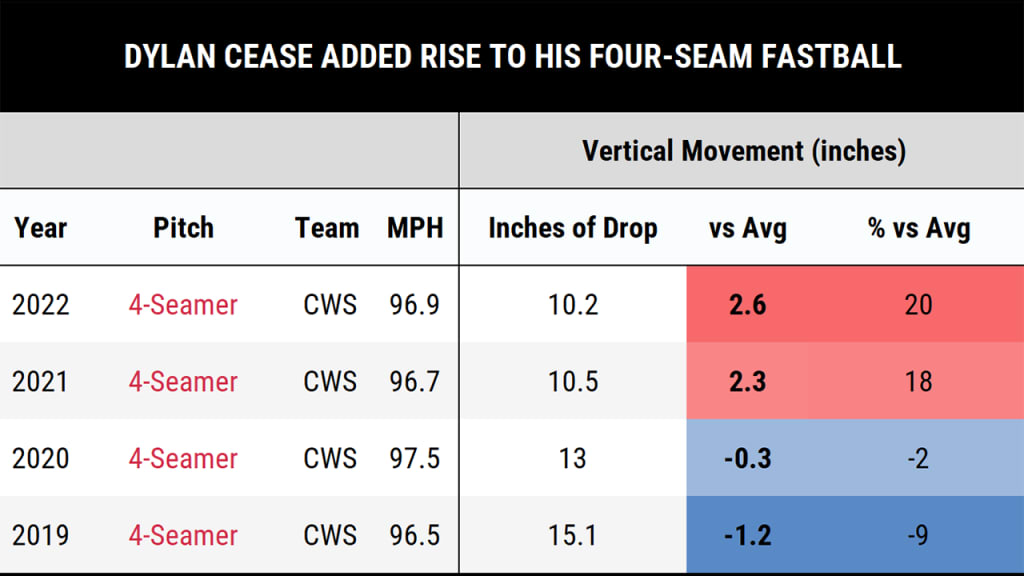

In 2019, Cease threw his fastball hard (at 96.5 MPH, it was one of the dozen hardest among any regular starting pitcher) and with excellent spin (87th percentile) and in such a way that it was routinely tattered by opposing batters, allowing the 7th-worst results of any pitcher who had at least 100 plate appearances end on them.

The “why” behind this isn’t that complicated, at least through the window of how we understand pitching over the last few years. Sure, he threw hard. Sure, it had spin. But the shape – and here we refer to terms like rise, sink, or cut – was bad. It’s not at all dissimilar to the story of Corbin Burnes, who also had a hard, high-spin, straight four-seamer that year .. and watched it get tattooed so thoroughly he all but dumped the pitch entirely on his way to stardom.

In Cease’s case, the numbers show that as a rookie, his four-seamer dropped 15 inches on the way to the plate, which is 1.2 inches less rise than average. If you want the rising action to miss bats, you want more rise than average. If you want sink to get grounders, you want way less rise. If you’re just in that nebulous middle zone, well, Major League batters can time up a straight fastball. And so they did.

Until, of course, they didn’t. Cease throws just as hard now (96.9 mph) as he did then (96.5 mph), and he’s added a little spin, but he always had spin. What he has now, thanks in part to mechanical changes as well as the efficiency in which he’s releasing the pitch – 65% as a rookie to 93% this year – is rise. Good rise.

How rare is that, to change the shape of a fastball that much?

We went back and looked at the hundreds of pitchers who had thrown at least 100 four-seamers both in 2019 and 2022, as Cease has. We identified those who had not only added the most rise against average but had managed to go from below-average to above-average while doing so. It wasn’t terribly difficult to find pitchers who had added an inch or so of extra rise in that time. A bunch of pitchers had managed to add two extra inches. But three or more? It’s a short list.

+3.8 inches // Dylan Cease

+3.6 inches // Jameson Taillon

+3.3 inches // Tyler Mahle

+3.3 inches // Tanner Scott

For Cease, what was a nearly-worst-in-baseball four-seamer in 2019-20 has dropped more than 140 points in slugging in the two seasons since. It moves more. It moves better. And, as you’re about to see, it’s thrown less.

2. THE SLIDER.

Over at Baseball Savant, you can look at a list of the most valuable pitches in baseball by run value, which assigns a value to every pitch of a plate appearance. That is, usually when you see that a pitch allowed this average or that slugging, it’s just talking about the final pitch of the at-bat. There’s clearly value in getting a first-pitch strike to turn the count in your favor, or having your 1-1 pitch become a 2-1 count rather than a 1-2, so that’s what this does. It’s quantity x quality.

With that as a background, do notice the top pitch of 2022 (negative numbers, for pitchers, are good):

That’s an incredibly good pitch atop a list of big stars with other incredibly good pitches. Unlike his fastball, it was effective from day one – in 2019, he allowed a mere .181 average and .373 slugging against – but it’s different now. So far in 2022, Cease has thrown it 931 times … and allowed all of six extra-base hits. He’s collected 103 strikeouts, the most in baseball on any pitch type.

But it’s different now, too. In 2019 and ‘20, Cease was throwing a slower, loopier slider – 85 mph with 6 inches more drop than average. That changed a little last year, and now it’s almost a different pitch entirely, because it’s harder (87 mph) and with only 2 inches extra drop. He’s even changing it within this current season, as he told the Athletic in June, because so far in August he’s throwing it a career-high 88 mph, with even less drop. Since he’s halved the horizontal break as well, it might be more akin to a cutter now, if anything.

As studies from Driveline Baseball have shown, [there’s] “almost no way to throw a bad breaking ball harder than 85.” He’s also using it as his primary pitch.

In fact, he’s throwing it so often, and so well, that barring major disaster, he’s going to end 2022 with the most valuable single slider season since tracking began in 2008.

3. THE CURVEBALL.

Ironically, the very first thing we noticed about Cease when he arrived in 2019 wasn’t his fastball or his slider. It was his curve, which appeared at the very top of the curveball drop leaderboards after just three Major League starts.

That’s still true today, where it’s No. 3 among all pitchers with 100 curves, and No. 1 among starters. Like the slider, it’s gained velocity as this season has progressed, going from 78.8 mph in April to a career-high 82.2 mph in August. Still, even though it’s only 5 mph slower than his slider, it drops 24 inches — yes, two feet — more. Talk about changing the eye level.

4. THE CHANGEUP

Clearly his fourth pitch – used just 3% of the time – we won’t spend a great deal of time on this weapon, one that might be evolving into more of a splitter, other than to point out that it’s going the opposite way, velocity-wise, of his two breaking balls. This one was 83.1 mph as a rookie, and it’s down to 77.7 mph now.

Remember that Cease throws a 96.9 mph four-seamer, and that most changeups work best playing off the four-seamer, and now he’s got a 19.2 mph velocity gap between the two. It’s the largest gap, by kind of a lot, of any pitcher in baseball. (Only one other pitcher, Cleveland reliever Eli Morgan, has even a 16 mph difference.)

When it works right, when he can make the changeup look like the fastball, you can see just how silly it makes hitters look, like then-Royal Andrew Benintendi earlier this season. It helps, too, that it breaks four times as much as it did when he was a rookie.